- Theodora

- (d. 548)Wife and inspiration of the Byzantine emperor Justinian (r. 527-565), who shared his rule and was an important source of strength for him until her death in 548. Although her background was not the usual one for an empress, Theodora rose from humble circumstances to play a critical role in Justinian's reign. She helped him survive the most difficult moment in his reign and played an important role in his religious and military programs. Her death from cancer on June 28, 548, was a terrible blow to the emperor, who was never the same after the loss of his beloved.Theodora is not only an important figure but, at least in her own time, also a controversial one. She was from most humble beginnings; her father was the animal trainer for the imperial arena, and she herself performed on the stage. In the late Roman and early Byzantine world, acting on the stage was deemed a most inglorious profession and a bar from marriage to a person of senatorial rank. Moreover, she was forced into prostitution on occasion to support her family, and, according to the sixth-century Byzantine historian and general Procopius, she was an excellent and insatiable prostitute. He notes in his Secret History that Theodora, while still a young and underdeveloped girl, acted as a sort of male prostitute and resided in a brothel. When she was older she continued life as a courtesan and would exhibit herself publicly. Procopius says that she would attend parties with ten men and lie with them in turn, then proceed to lie with the other partygoers, and then lie with their servants. Not only, Procopius tells us, was she incredibly promiscuous but she was also without shame. She would perform a special act in the theater where she would lie almost completely naked, have servants sprinkle barley grains over her private parts, and have geese come along and pick the grains up with their bills.

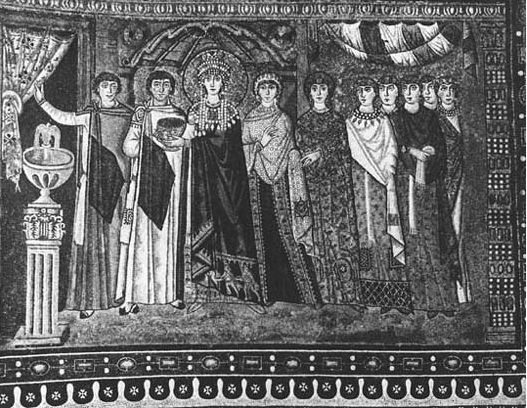

Mosaic of Theodora from the Church of San Vitale, Ravenna (Hulton Archive)Procopius's account clearly is an exaggeration and was included in a work not intended for public consumption. Although The Secret History offers a gross caricature of the empress, it does contain a kernel of truth-Theodora was an actor and, probably, a prostitute. Her family history was an unfortunate one. Her father, Akakios, the bear keeper for the Green faction-one of two factions in Constantinople that provided charioteers and other performers for the games in the arena and that had extensive support networks throughout the city-died while Theodora was still a girl. Her mother remarried in the hopes that her new husband would be awarded the position. Unfortunately for Theodora, her two sisters, and her mother this did not happen, and only after public pleading by her mother or Theodora and her sisters did their stepfather receive the position. But the award was made by the Blues, the rival faction to the Greens, an action that Theodora never forgot. Life, however, remained difficult, and Theodora performed on the stage, where her sharp wit and talent won her popularity.Unwilling to settle for the difficult life of the stage, Theodora aimed higher and became the mistress of Hecebolus, a high government minister and governor of a minor province in Africa. Her relationship with Hecebolus brought great changes to her life. She accompanied him to Africa, but their relationship soon soured, as Theodora's biting wit proved too much for the older and duller Hecebolus to endure. She was sent away after a terrible fight and left to her own resources. Procopius says that she turned to prostitution, but again caution should be exercised in accepting his bitter commentary. It is certain that Theodora spent time in Alexandria, where she met a number of leading Monophysite clergy. At this point, under the influence of the pious Monophysites, Theodora underwent a religious conversion and renounced her former way of life. She managed to find her way back to Constantinople, where she established herself in a small house, practicing the honorable and very traditional profession of sewing.It was at this point that she met Justinian, nephew of the emperor Justin and heir apparent. Despite her rather checkered past, Theodora possessed a number of qualities that attracted Justinian. Not the least of these qualities was her physical beauty. Contemporary accounts comment on her attractiveness, and mosaics and sculpture confirms this. She was petite and had an oval face with large black eyes-features that served her on the stage and before the emperor. But her qualities went far beyond physical beauty; it was her personal qualities that inspired such great love and devotion from Justinian. Even her harshest critic, Procopius, noted that she was very clever and had a biting wit. Indeed, in his History of the Wars Procopius presents a most favorable portrait of Theodora that is in stark contrast to the portrait in The Secret History. And another contemporary, John Lydus, noted that she was more intelligent than anyone in the world. She also possessed some learning and culture that enabled her to fit in Justinian's world. But more than learning and intelligence, Theodora possessed great self-confidence and nerves of steel. Justinian himself was a man capable of prodigious amounts of work, but he sometimes lacked resolve, and it was Theodora who provided that strength of will.Justinian, fifteen years her senior, was deeply smitten by Theodora and made her his mistress and shortly thereafter planned to marry her. There were several obstacles to the marriage: Theodora's humble birth, the legal barrier against an actor marrying a senator, and the reigning empress, Euphemia, who absolutely forbade the relationship. Theodora was elevated to the patriciate by Justin, Justinian's uncle and the emperor. Euphemia's death in 524 eliminated another of the obstacles to marriage. Justin, lastly, issued a law allowing actors who had renounced their previous lifestyle, had lived honorably, and had received high dignity to marry members of the senatorial aristocracy. In 525 Justinian and Theodora married, and in 527, at the death of Justin, they ascended to the imperial dignity.In many ways Theodora exercised great influence over her husband and his reign. Her most important moment, however, came during the Nika Revolt in 532, which nearly toppled Justinian's government. The revolt broke out in January on the heels of yet another riot between the Greens and Blues. Violence between the two factions was not uncommon in Constantinople, but this riot took on more serious implications because leaders of the two factions were arrested and condemned to death. The factions were united by the desire to save their leaders and also by dissatisfaction with taxes, bread distribution, and government agents. The government's failure to respond effectively to the demands of the Blues and Greens and unwillingness to release the leaders led to great violence. The factions stormed the City Prefect's palace, killing police and releasing prisoners as they went. Shouting "Nika the Blues! Nika the Greens!" (Nika meaning win or conquer), the rioters destroyed much of the city. The revolt was so serious that the crowds, directed in part by ambitious senators who sought to exploit the situation, proclaimed a rival emperor, the senator Hypatius.Justinian's efforts to suppress the revolt were half-hearted and ineffective, but more deliberate attempts depended upon palace guards whose loyalty was uncertain. Justinian's personal appearance before the crowd did little but alienate them further. At that crucial moment Justinian seems to have lost his nerve and ordered flight. Theodora stood before her husband's council and made, according to Procopius, the following speech:Whether or not a woman should give an example of courage to men, is neither here nor there. At a moment of desperate danger one must do what one can. I think that flight, even if it brings us to safety, is not in our interest. Every man born to see the light of day must die. But that one who has been emperor should become an exile I cannot bear. May I never be without the purple I wear, nor live to see the day when men do not call me "Your Majesty." If you wish safety, my Lord, that is an easy matter. We are rich, and there is the sea, and yonder our ships. But consider whether if you reach safety you may not desire to exchange that safety for death. As for me, I like the old saying, that the purple is the nobles shroud. (Procopius, History of the Wars I.24.33-37, cited in Robert Browning, Justinian and Theodora, p. 72.)Theodora's strength gave Justinian the resolve he needed, and a plan was hatched by Justinian and his loyal generals. Using German mercenaries, the generals infiltrated the crowd of rebels in the Hippodrome and successfully massacred 30,000 people. The revolt was suppressed. The rival emperor was captured and brought before Justinian, who was about to commute the death sentence of his old friend to permanent exile when Theodora convinced her husband to execute his rival. The revolt had ended, and Justinian survived, thanks to his loyal generals and, most especially, Theodora.Theodora's most dramatic impact on Justinian's reign occurred during the Nika Revolt, but she influenced Justinian's domestic and foreign policy throughout their lives together. She clearly had her favorites among Justinian's civil and military staff, and those whom she disliked suffered. She orchestrated the fall of two of his ministers whom she despised. Priscus, an imperial secretary who had enriched himself at public expense, was tonsured and packed away to a monastery by the empress. John of Cappadocia, an imperial financial minister who had risen from humble beginnings, was another victim. Although he was an honorable minister, his methods were brutal, and his deposition was demanded during the Nika Revolt. He was implicated in a plot against Justinian and accused of the murder of a bishop. His methods and possible betrayal of the emperor made him an enemy of Theodora, who forced Justinian to believe the worst about John. Although Theodora struck out ruthlessly against those she thought unfaithful to Justinian and those who, like Hypatius, openly opposed him, Theodora was also an important benefactor. She was a staunch ally of the general Narses, who earned her favor by his defense of Justinian in 532. She protected him and promoted his cause during the wars in Italy.Theodora not only influenced personnel decisions but also presented a more human face to the imperial dignity by her largesse. With Justinian she indulged in acts of charity that were functions of both imperial responsibility and Christian duty. On numerous occasions, Theodora, with and without her husband, made lavish charitable donations. Following the devastating earthquake in Antioch in 528, Justinian and Theodora, all contemporary records attest, sent great amounts of money to help rebuild the city. On a trip to northwestern Asia Minor, Theodora offered large donations to churches along her route. She also took special care of poor young women who had been sold into a life of prostitution. On one occasion she called the owners of the brothels to the court, reprimanded them for their activities, and purchased the girls from them out of her own purse. She returned them to their parents and also established a convent where they could retire.The empress also played a critical role in religious affairs in the empire. It was her favorite Vigilius who succeeded to the papal throne in 537, although not simply because he was her favorite. She conspired in the elevation of Vigilius to the office of the papacy above all because she thought he would be a more pliable pope on religious matters important to her and the emperor. But more than that she offered protection to an important religious minority in the empire. As the emperor, Justinian was the protector of the faith and defender of orthodoxy. Consequently, he enforced orthodox Christian belief and ordered the persecution of heretics, including the execution of many Manichaeans of high social rank. The empire, however, faced a serious division over the nature of Jesus Christ that threatened imperial unity and relations with Rome. The largest minority sect in the empire was that of the Monophysites, who were particularly numerous in the wealthy and populous region of Syria. Theodora, a devout Monophysite Christian, defended and protected her co-religionists. She encouraged the promotion of Monophysites or their sympathizers to positions of ecclesiastical importance and protected Monophysites in her private chapel. She also may have influenced Justinian's publication of a profession of faith that sought a common ground between orthodox Catholic doctrine and Monophysite doctrine.Theodora's impact may also have been felt on Justinian's foreign policy. One of the emperor's great dreams was to restore Italy to imperial control, and the situation on the peninsula after the death of the great Gothic king Theodoric in 526 afforded him an opportunity. Theodoric was succeeded by his eight-year-old grandson, Athalaric, under the regency of his mother and Theodoric's daughter, Amalaswintha. The regent was a cultured, educated, and ambitious woman who found herself at odds with much of the Gothic nobility. Facing conspiracy from the nobility, especially after the death of her son, Amalaswintha found an ally in Justinian, whom she nearly visited in Constantinople in 532. For the emperor, a close alliance with Amalaswintha provided an entry into Italian affairs and the possible extension of imperial control. Her talent and royal blood made her an attractive marriage candidate, a fact not lost on anyone in the imperial capital-especially Theodora. The Gothic queen, however, never made the trip east and was eventually imprisoned by her rivals in Italy. It is at this point that the possible influence of Theodora can be seen.Justinian sent an envoy to protest the imprisonment, threatening war if anything should happen to the queen. According to Procopius, the envoy received a second message from Theodora, instructing him to inform the Gothic king, Theodohad, that Justinian would do nothing should anything happen to Amalaswintha. And not long after Amalaswintha was murdered. Justinian had his pretext to invade Italy. Theodora provided this pretext, Procopius tells us, out of jealousy, but it is likely that Justinian was aware of the second letter and approved of it. Whether he did or not is conjecture, but clearly he benefited from the letter, just as he benefited from Theodora's inner strength and good political sense throughout their lives together.See alsoBibliography♦ Browning, Robert. Justinian and Theodora. Rev. ed. London: Thames and Hudson, 1987.♦ Bury, John B. History of the Later Roman Empire: From the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian. Vol. 2. 1923. Reprint, New York: Dover, 1959.♦ Clark, Gillian. Women in Late Antiquity: Pagan and Christian Lifestyles. Oxford: Clarendon, 1993.♦ Obolensky, Dmitri. The Byzantine Commonwealth: Eastern Europe, 500-1453. New York: Praeger, 1971.

Mosaic of Theodora from the Church of San Vitale, Ravenna (Hulton Archive)Procopius's account clearly is an exaggeration and was included in a work not intended for public consumption. Although The Secret History offers a gross caricature of the empress, it does contain a kernel of truth-Theodora was an actor and, probably, a prostitute. Her family history was an unfortunate one. Her father, Akakios, the bear keeper for the Green faction-one of two factions in Constantinople that provided charioteers and other performers for the games in the arena and that had extensive support networks throughout the city-died while Theodora was still a girl. Her mother remarried in the hopes that her new husband would be awarded the position. Unfortunately for Theodora, her two sisters, and her mother this did not happen, and only after public pleading by her mother or Theodora and her sisters did their stepfather receive the position. But the award was made by the Blues, the rival faction to the Greens, an action that Theodora never forgot. Life, however, remained difficult, and Theodora performed on the stage, where her sharp wit and talent won her popularity.Unwilling to settle for the difficult life of the stage, Theodora aimed higher and became the mistress of Hecebolus, a high government minister and governor of a minor province in Africa. Her relationship with Hecebolus brought great changes to her life. She accompanied him to Africa, but their relationship soon soured, as Theodora's biting wit proved too much for the older and duller Hecebolus to endure. She was sent away after a terrible fight and left to her own resources. Procopius says that she turned to prostitution, but again caution should be exercised in accepting his bitter commentary. It is certain that Theodora spent time in Alexandria, where she met a number of leading Monophysite clergy. At this point, under the influence of the pious Monophysites, Theodora underwent a religious conversion and renounced her former way of life. She managed to find her way back to Constantinople, where she established herself in a small house, practicing the honorable and very traditional profession of sewing.It was at this point that she met Justinian, nephew of the emperor Justin and heir apparent. Despite her rather checkered past, Theodora possessed a number of qualities that attracted Justinian. Not the least of these qualities was her physical beauty. Contemporary accounts comment on her attractiveness, and mosaics and sculpture confirms this. She was petite and had an oval face with large black eyes-features that served her on the stage and before the emperor. But her qualities went far beyond physical beauty; it was her personal qualities that inspired such great love and devotion from Justinian. Even her harshest critic, Procopius, noted that she was very clever and had a biting wit. Indeed, in his History of the Wars Procopius presents a most favorable portrait of Theodora that is in stark contrast to the portrait in The Secret History. And another contemporary, John Lydus, noted that she was more intelligent than anyone in the world. She also possessed some learning and culture that enabled her to fit in Justinian's world. But more than learning and intelligence, Theodora possessed great self-confidence and nerves of steel. Justinian himself was a man capable of prodigious amounts of work, but he sometimes lacked resolve, and it was Theodora who provided that strength of will.Justinian, fifteen years her senior, was deeply smitten by Theodora and made her his mistress and shortly thereafter planned to marry her. There were several obstacles to the marriage: Theodora's humble birth, the legal barrier against an actor marrying a senator, and the reigning empress, Euphemia, who absolutely forbade the relationship. Theodora was elevated to the patriciate by Justin, Justinian's uncle and the emperor. Euphemia's death in 524 eliminated another of the obstacles to marriage. Justin, lastly, issued a law allowing actors who had renounced their previous lifestyle, had lived honorably, and had received high dignity to marry members of the senatorial aristocracy. In 525 Justinian and Theodora married, and in 527, at the death of Justin, they ascended to the imperial dignity.In many ways Theodora exercised great influence over her husband and his reign. Her most important moment, however, came during the Nika Revolt in 532, which nearly toppled Justinian's government. The revolt broke out in January on the heels of yet another riot between the Greens and Blues. Violence between the two factions was not uncommon in Constantinople, but this riot took on more serious implications because leaders of the two factions were arrested and condemned to death. The factions were united by the desire to save their leaders and also by dissatisfaction with taxes, bread distribution, and government agents. The government's failure to respond effectively to the demands of the Blues and Greens and unwillingness to release the leaders led to great violence. The factions stormed the City Prefect's palace, killing police and releasing prisoners as they went. Shouting "Nika the Blues! Nika the Greens!" (Nika meaning win or conquer), the rioters destroyed much of the city. The revolt was so serious that the crowds, directed in part by ambitious senators who sought to exploit the situation, proclaimed a rival emperor, the senator Hypatius.Justinian's efforts to suppress the revolt were half-hearted and ineffective, but more deliberate attempts depended upon palace guards whose loyalty was uncertain. Justinian's personal appearance before the crowd did little but alienate them further. At that crucial moment Justinian seems to have lost his nerve and ordered flight. Theodora stood before her husband's council and made, according to Procopius, the following speech:Whether or not a woman should give an example of courage to men, is neither here nor there. At a moment of desperate danger one must do what one can. I think that flight, even if it brings us to safety, is not in our interest. Every man born to see the light of day must die. But that one who has been emperor should become an exile I cannot bear. May I never be without the purple I wear, nor live to see the day when men do not call me "Your Majesty." If you wish safety, my Lord, that is an easy matter. We are rich, and there is the sea, and yonder our ships. But consider whether if you reach safety you may not desire to exchange that safety for death. As for me, I like the old saying, that the purple is the nobles shroud. (Procopius, History of the Wars I.24.33-37, cited in Robert Browning, Justinian and Theodora, p. 72.)Theodora's strength gave Justinian the resolve he needed, and a plan was hatched by Justinian and his loyal generals. Using German mercenaries, the generals infiltrated the crowd of rebels in the Hippodrome and successfully massacred 30,000 people. The revolt was suppressed. The rival emperor was captured and brought before Justinian, who was about to commute the death sentence of his old friend to permanent exile when Theodora convinced her husband to execute his rival. The revolt had ended, and Justinian survived, thanks to his loyal generals and, most especially, Theodora.Theodora's most dramatic impact on Justinian's reign occurred during the Nika Revolt, but she influenced Justinian's domestic and foreign policy throughout their lives together. She clearly had her favorites among Justinian's civil and military staff, and those whom she disliked suffered. She orchestrated the fall of two of his ministers whom she despised. Priscus, an imperial secretary who had enriched himself at public expense, was tonsured and packed away to a monastery by the empress. John of Cappadocia, an imperial financial minister who had risen from humble beginnings, was another victim. Although he was an honorable minister, his methods were brutal, and his deposition was demanded during the Nika Revolt. He was implicated in a plot against Justinian and accused of the murder of a bishop. His methods and possible betrayal of the emperor made him an enemy of Theodora, who forced Justinian to believe the worst about John. Although Theodora struck out ruthlessly against those she thought unfaithful to Justinian and those who, like Hypatius, openly opposed him, Theodora was also an important benefactor. She was a staunch ally of the general Narses, who earned her favor by his defense of Justinian in 532. She protected him and promoted his cause during the wars in Italy.Theodora not only influenced personnel decisions but also presented a more human face to the imperial dignity by her largesse. With Justinian she indulged in acts of charity that were functions of both imperial responsibility and Christian duty. On numerous occasions, Theodora, with and without her husband, made lavish charitable donations. Following the devastating earthquake in Antioch in 528, Justinian and Theodora, all contemporary records attest, sent great amounts of money to help rebuild the city. On a trip to northwestern Asia Minor, Theodora offered large donations to churches along her route. She also took special care of poor young women who had been sold into a life of prostitution. On one occasion she called the owners of the brothels to the court, reprimanded them for their activities, and purchased the girls from them out of her own purse. She returned them to their parents and also established a convent where they could retire.The empress also played a critical role in religious affairs in the empire. It was her favorite Vigilius who succeeded to the papal throne in 537, although not simply because he was her favorite. She conspired in the elevation of Vigilius to the office of the papacy above all because she thought he would be a more pliable pope on religious matters important to her and the emperor. But more than that she offered protection to an important religious minority in the empire. As the emperor, Justinian was the protector of the faith and defender of orthodoxy. Consequently, he enforced orthodox Christian belief and ordered the persecution of heretics, including the execution of many Manichaeans of high social rank. The empire, however, faced a serious division over the nature of Jesus Christ that threatened imperial unity and relations with Rome. The largest minority sect in the empire was that of the Monophysites, who were particularly numerous in the wealthy and populous region of Syria. Theodora, a devout Monophysite Christian, defended and protected her co-religionists. She encouraged the promotion of Monophysites or their sympathizers to positions of ecclesiastical importance and protected Monophysites in her private chapel. She also may have influenced Justinian's publication of a profession of faith that sought a common ground between orthodox Catholic doctrine and Monophysite doctrine.Theodora's impact may also have been felt on Justinian's foreign policy. One of the emperor's great dreams was to restore Italy to imperial control, and the situation on the peninsula after the death of the great Gothic king Theodoric in 526 afforded him an opportunity. Theodoric was succeeded by his eight-year-old grandson, Athalaric, under the regency of his mother and Theodoric's daughter, Amalaswintha. The regent was a cultured, educated, and ambitious woman who found herself at odds with much of the Gothic nobility. Facing conspiracy from the nobility, especially after the death of her son, Amalaswintha found an ally in Justinian, whom she nearly visited in Constantinople in 532. For the emperor, a close alliance with Amalaswintha provided an entry into Italian affairs and the possible extension of imperial control. Her talent and royal blood made her an attractive marriage candidate, a fact not lost on anyone in the imperial capital-especially Theodora. The Gothic queen, however, never made the trip east and was eventually imprisoned by her rivals in Italy. It is at this point that the possible influence of Theodora can be seen.Justinian sent an envoy to protest the imprisonment, threatening war if anything should happen to the queen. According to Procopius, the envoy received a second message from Theodora, instructing him to inform the Gothic king, Theodohad, that Justinian would do nothing should anything happen to Amalaswintha. And not long after Amalaswintha was murdered. Justinian had his pretext to invade Italy. Theodora provided this pretext, Procopius tells us, out of jealousy, but it is likely that Justinian was aware of the second letter and approved of it. Whether he did or not is conjecture, but clearly he benefited from the letter, just as he benefited from Theodora's inner strength and good political sense throughout their lives together.See alsoBibliography♦ Browning, Robert. Justinian and Theodora. Rev. ed. London: Thames and Hudson, 1987.♦ Bury, John B. History of the Later Roman Empire: From the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian. Vol. 2. 1923. Reprint, New York: Dover, 1959.♦ Clark, Gillian. Women in Late Antiquity: Pagan and Christian Lifestyles. Oxford: Clarendon, 1993.♦ Obolensky, Dmitri. The Byzantine Commonwealth: Eastern Europe, 500-1453. New York: Praeger, 1971.

Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe. 2014.